30. The Early Noughties Revolution

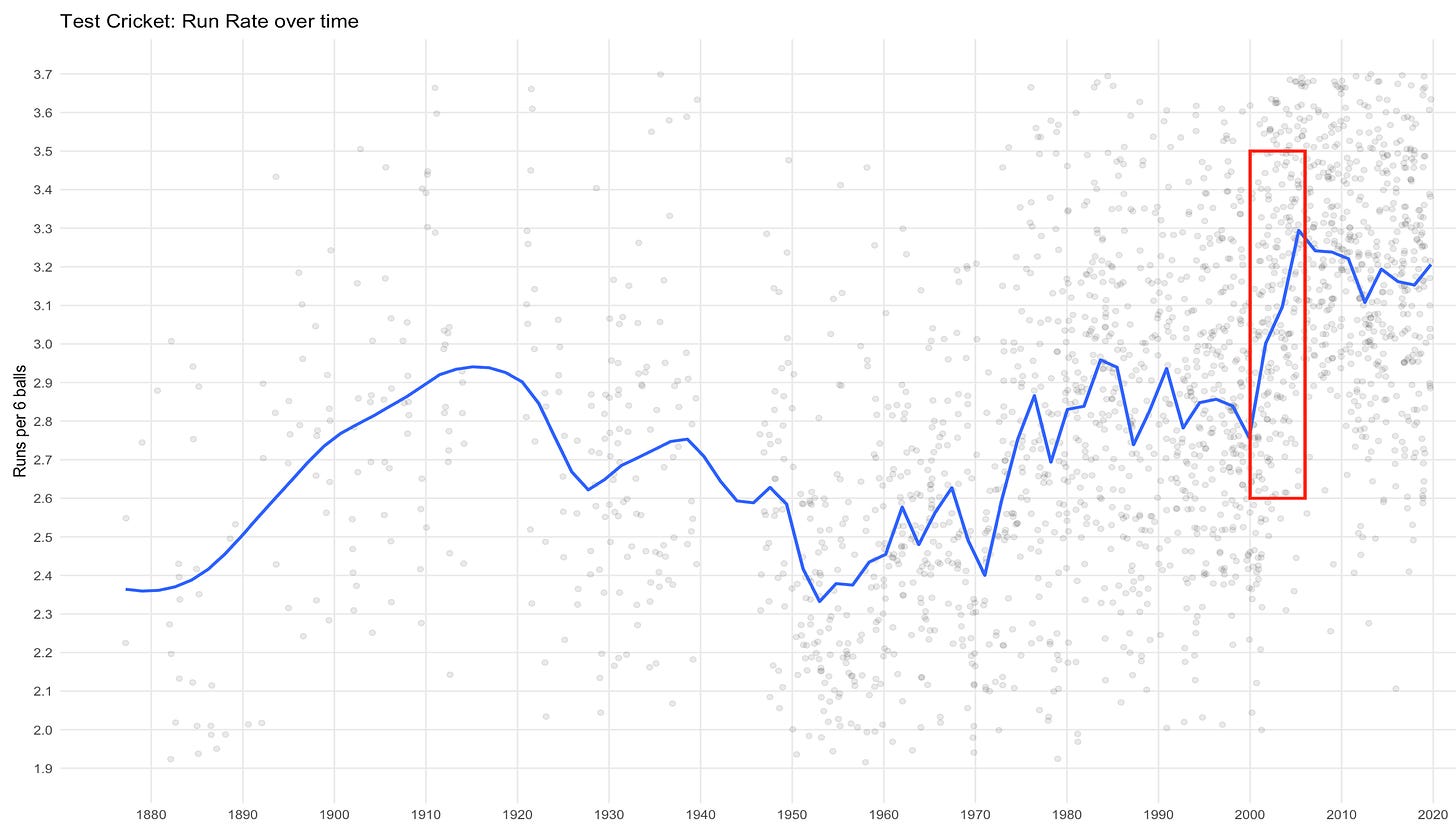

Rate of scoring in Test cricket dramatically increased in the first few years of this century, before slowing down

Test cricket went through a fundamental change in the first years of this century. Having plodded along at an average of 2.8 runs per over for the previous 25 years, Test cricket exploded at the turn of the millennium, soon reaching an average of 3.5 runs per over.

The good times haven’t lasted, though, as cricket has become slower, with the run rate nowadays averaging around 3.2.

It is not straightforward to analyse why Test cricket sped up in the early noughties, and then stagnated. If we were to split the above graph by innings of the match, there is no real signal there (except that fourth innings run rates didn’t really grow by too much in this period). Even splitting by country doesn’t give a conclusive result - most major Test playing countries showed a spike in run rate in that period.

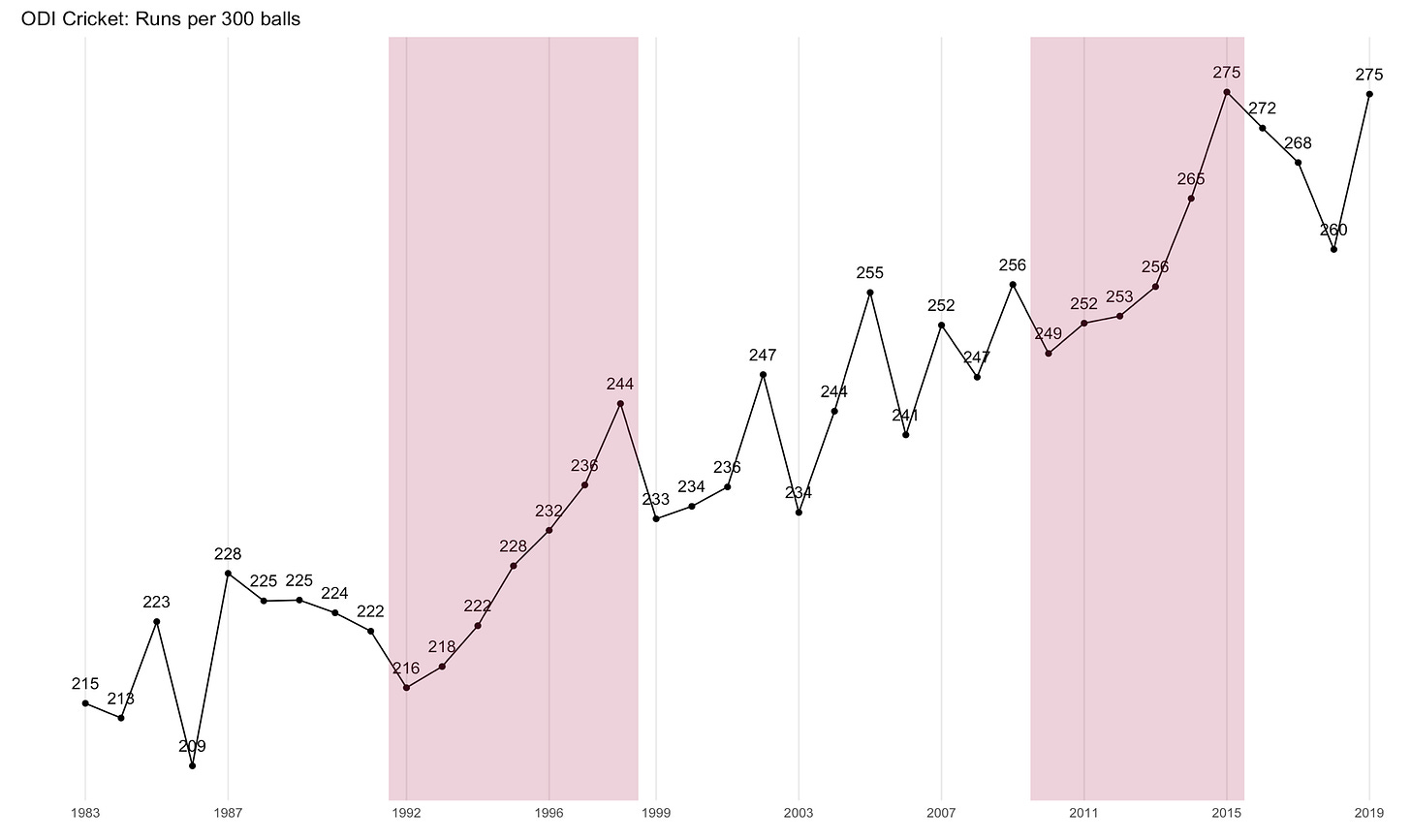

One clue comes from our analysis of one day international cricket - the nineties saw the first “bull run” in ODI run rates. That was primarily driven by teams pushing up their best and fastest scoring batsmen to open the innings - which meant that they scored at a fast pace for a longer period of the innings. With Test cricket not having limited overs, that explanation doesn’t directly translate.

However, it is likely that as scoring rates in ODI went up, batsmen started taking the same approach to Tests as well. It is interesting to note that the Test scoring rate started climbing up just when the first ODI bull run had ended, though we should remember that in the late 90s, most players played both Tests and ODIs.

There is another story that can explain why Test match scoring rates shot up in the early 2000s - it was the period of coming together of a number of fast-scoring, and prolific, batsmen.

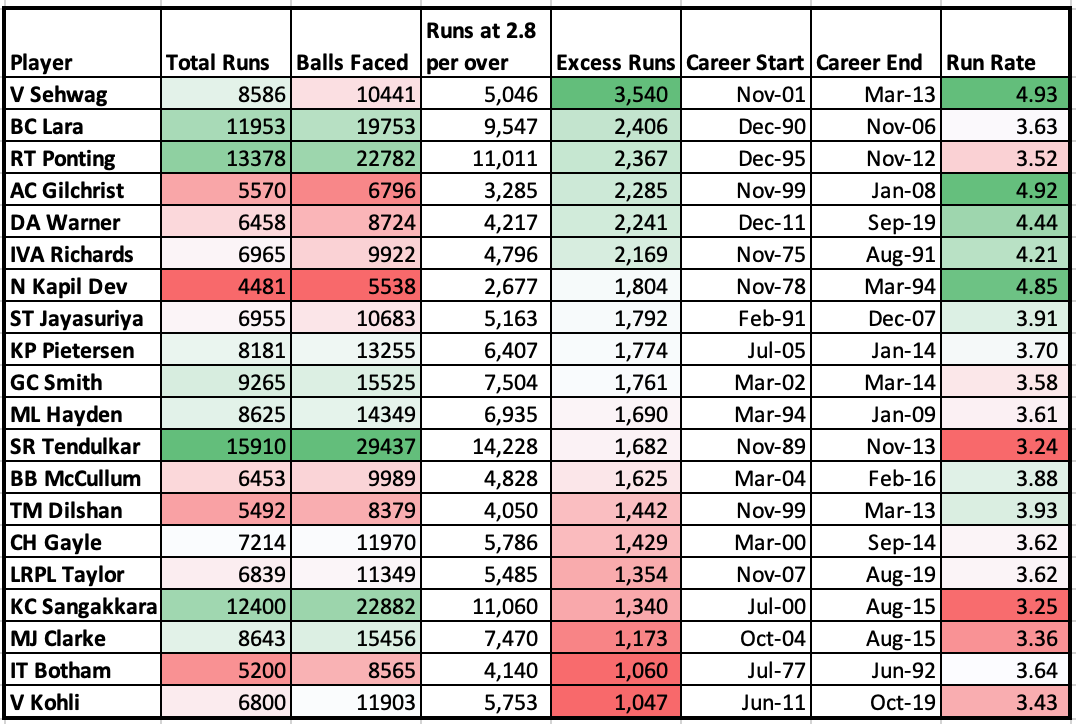

I propose a measure to identify fast-scoring and prolific batsmen. I call it “Excess Runs”. The idea is that a “normal Test batsman” plays at 2.8 runs per over (the scoring rate in 1975-2000), or 47 runs per 100 balls. Thus, for a batsman, the “par runs” is 47 runs for every 100 balls faced. Given the number of balls a player has faced in Test cricket, we calculate the “par runs”, and the actual number of runs scored minus par is the batsman’s Excess Runs.

For example, Virender Sehwag faced 10,441 balls in Test cricket. Batting at 2.8 runs per over, he should have scored 5046 runs. Instead, he made 8586 runs, giving 3540 Excess Runs. Sachin Tendulkar faced 29,437 balls. Had he scored at 2.8 per over, he would’ve made 14,228 runs. He ended up scoring 15,910, giving an excess of 1682.

Note that Excess Runs is a “volume measure” - it is a product of a player’s longevity and the rate of scoring. A player who scores a few quick hundreds will not have a very high score, and neither will someone who played a long but slow career. Sehwag tops the Excess Runs measure only because he both played incredibly quickly, and made lots of runs.

Anyway, here are the top 20 batsmen of all time in terms of Excess Runs.

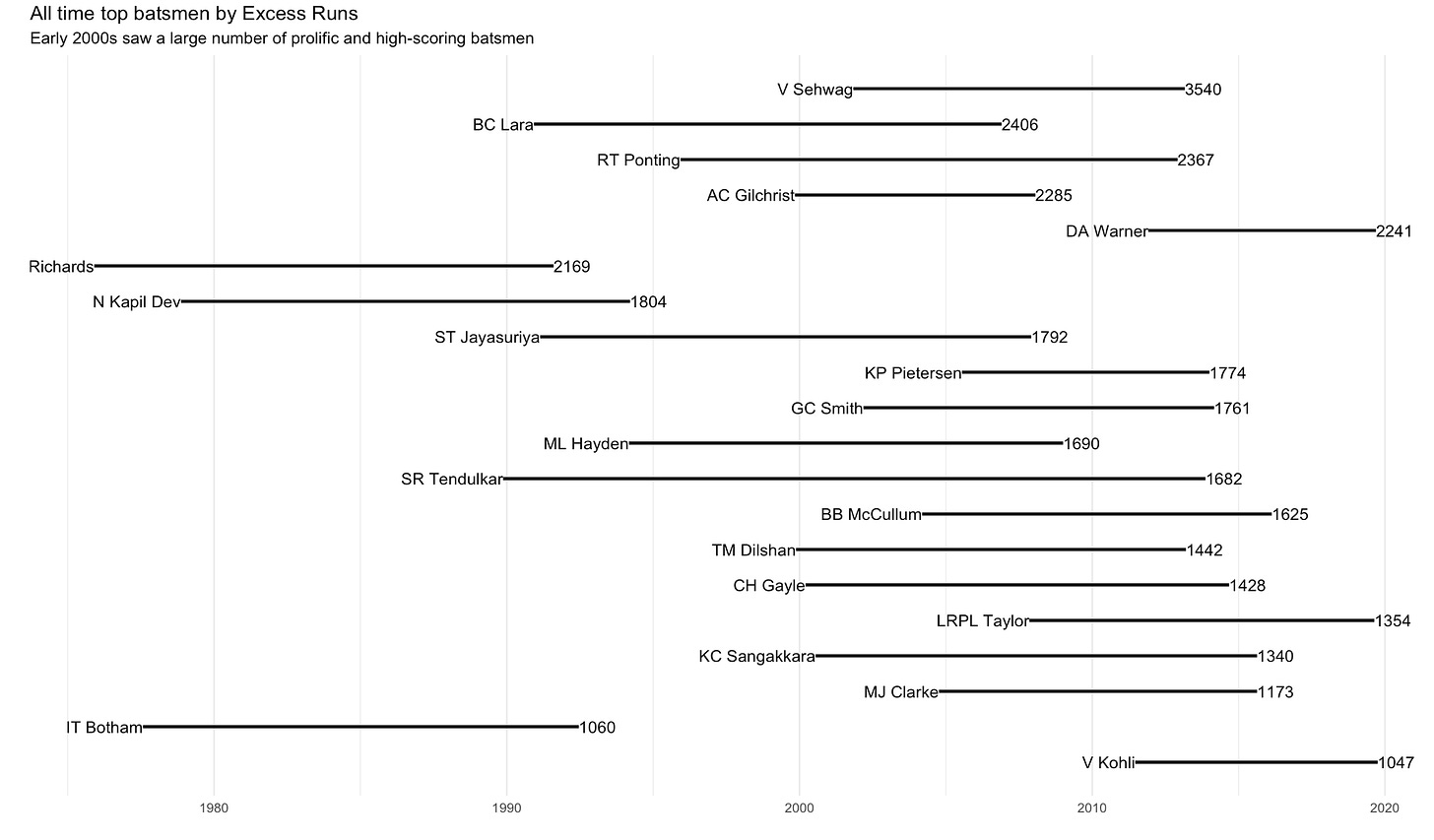

They together account for 35% of all Excess Runs ever scored in Test cricket. Do you notice something about their career spans? An incredible number of these played in the 2000-2006 time period. This graph might make this more clear.

The 80s had basically 3 prolific and fast-scoring batsmen - Viv Richards, Kapil Dev and Ian Botham. All of them ended their careers in the early 90s, and in the 90s we had Brian Lara, Ricky Ponting, Sachin Tendulkar and Sanath Jayasuriya (Matthew Hayden made his debut in the early 90s, but didn’t play much until the late 90s when Mark Taylor retired).

In recent times, we have David Warner, Ross Taylor and Virat Kohli. The rest of the batsmen here essentially belong to the 2000-2010 decade. The sheer volume of high-scoring and prolific batsmen who played in that period means that Test run rates shot up in that period. And once the likes of Brian Lara, Adam Gilchrist and Matthew Hayden retired in the late 2000s, there is a slight drop in the run rates.

Finally, we need to ask ourselves why Test cricket has slowed down after the retirement of the “class of the 2000s”. Why is it that even as ODI cricket has gotten faster, Test cricket has slowed down in the last decade or so?

I don’t have data to offer yet, but can offer one hypothesis - the last 10 years has seen increased specialisation. Players are increasingly specialising between the long and short forms - Chris Gayle, for example, has been prolific in ODI and T20 cricket, but hasn’t played a Test for five years now. The conditions are also different - pitches for limited overs are far more friendly to batsmen, as Jason Roy’s struggles in the recent Ashes series illustrate.

As a consequence, even as limited overs scoring rates have been going up, the explosive batsmen from that format have been unable to carry on their explosiveness to Tests as well. And with Tests being played more by Test specialists, and the more steady limited overs players (such as Kohli or Steve Smith), scoring rates have gone down.

When India decided to use their most explosive ODI batsman - Rohit Sharma - to open the innings in Test cricket, there was an explicit comparison made with Virender Sehwag. It remains to be seen if Rohit’s success in his new role will spur another spike in Test cricket scoring rates.