The World Cup begins in England in three weeks’ time, and this year so far the two and quarter ODIs in England have produced runs at a rate of 372 per 300 balls. Last year, in an ODI in Trent Bridge, England had smashed a monumental 481 against Australia. This has purists worried about what might possibly be an incredibly high scoring World Cup.

Until I started writing this piece, my explanation for the 481 and other high scores in England last year had been that it was an incredibly hot summer in England last year. I was living in London at the time, and most days in July and early August were intolerable. As it happens, summer is already over this year in Bangalore (where April is the hottest month), and there was only one day that was comparable to the discomfort of last summer in London. Yes, I’m an Indian cribbing about the heat of the English Summer!

I was in London the previous summer as well, but that was a “normal English summer” barring one heat wave that happened to coincide with the finals of the Champions Trophy between India and Pakistan. In hindsight, that makes Virat Kohli’s decision to elect to field in that game puzzling.

What happened in 2015?

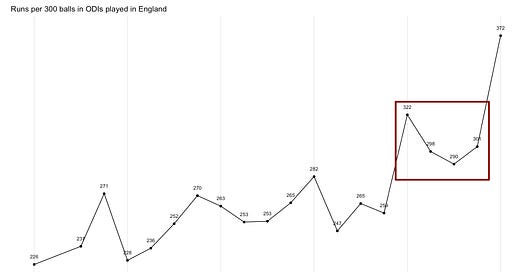

England was a “normal” one-day venue until 2014, with run-scoring in the range of 250-260 per 300 balls in the preceding 10 years. And then suddenly the number shot up to 322 in 2015, when Australia and New Zealand toured. The number did drop slightly in 2016-18, but England has remained a high-scoring venue.

(As an aside, reader Kesavan pointed out that the decline in run-scoring after 2015 is a consequence of the laws being changed back to allow five fielders outside the circle in all non-powerplay overs. Only four fielders had been allowed outside the circle in the 2011-15 period)

This sudden increase in scoring rate in England from 2015 onwards is not easy to explain. There were no rule changes in the beginning of the year that favoured batsmen. The balls were the same as the previous years. There was no drastic change in the mix of venues used for the 2015 games.

What did happen in 2015 was that England overhauled its ODI lineup following the debacle at the World Cup earlier that year, when they failed to get out of their group. Test specialists such as James Anderson, Stuart Broad and Ian Bell were dropped. Hitters such as Jason Roy, Alex Hales, Ben Stokes and Jonny Bairstow were brought in. Joe Root and James Taylor did not play in the same lineup after that. And if we look at the way teams constructed innings in games played in England over the years, 2015 marks a massive difference.

The traditional way of building an ODI innings is to bat steadily until over 40, and then go for the slog. That is how, for example, Pakistan approached and won the 1992 World Cup. And while ODI batting sped up in the 1990s thanks to “pinch hitting”, the overall approach remained the same.

Even in England, we see that until 2013, it was common to bat safely until over 40 and then slog in the last 10. In 2014, we see a slight change to the formula where the slogging started in overs 31-40. In 2015, England’s new top order (Roy and Hales, followed by Joe Root and Eoin Morgan) started hitting at a run a ball right from the beginning. New Zealand, their first opponents at home that year, responded in kind with Martin Guptill, Brendon McCullum and Kane Williamson. And a new way of batting in England got set (Australia, the other team to play in England that year, continued to bat traditionally relying on a strong slog).

Interestingly, if we look at the same graphs for games played everywhere, the difference between 2014 and 2015 doesn’t register. In that sense, we should credit the massive increase in run-scoring rate in England in 2015 to its new way of thinking followed by the World Cup debacle, with the side packed with hitters and the openers getting the licence to go for it from ball one.

This is the sort of theme that my friend Amit Varma frequently talks about in his writings on sport - sometimes there is an arbitrage waiting to get picked off because nobody really thought that things could be done differently. The conventional view in ODI cricket, even after the pinch hitting of the 1990s, was to build the innings through the first 40 overs and then start slogging.

England’s crisis after the World Cup meant that they experimented with the strategy of having a side with all hitters, and getting them to bat aggressively throughout the innings (there is no let-up in scoring rate in the middle of the innings in 2015). The strategy worked, and showed that it is possible to make very big scores in England through a consistent hitting approach.

Other teams followed the strategy, may be not to the same extent, and we got a high-scoring Champions Trophy in 2017. And no team has yet been able to discover a hole in the strategy, so we will most likely get a high scoring World Cup in 2019 as well. The purist may not enjoy this turn, but it appears to me that this high-scoring phase is the result of a well-thought-out strategy. So let us enjoy it while it lasts!

If you liked this, please consider subscribing. And share it with whoever you think will like it. Also, write back with your comments and suggestions on the newsletter, and today’s edition.