13. Running out of run outs

Run outs are becoming more and more rare in One Day International cricket. In 2004, there would be an average of 0.8 runouts in an innings of 300 balls. The number is half of that in 2019.

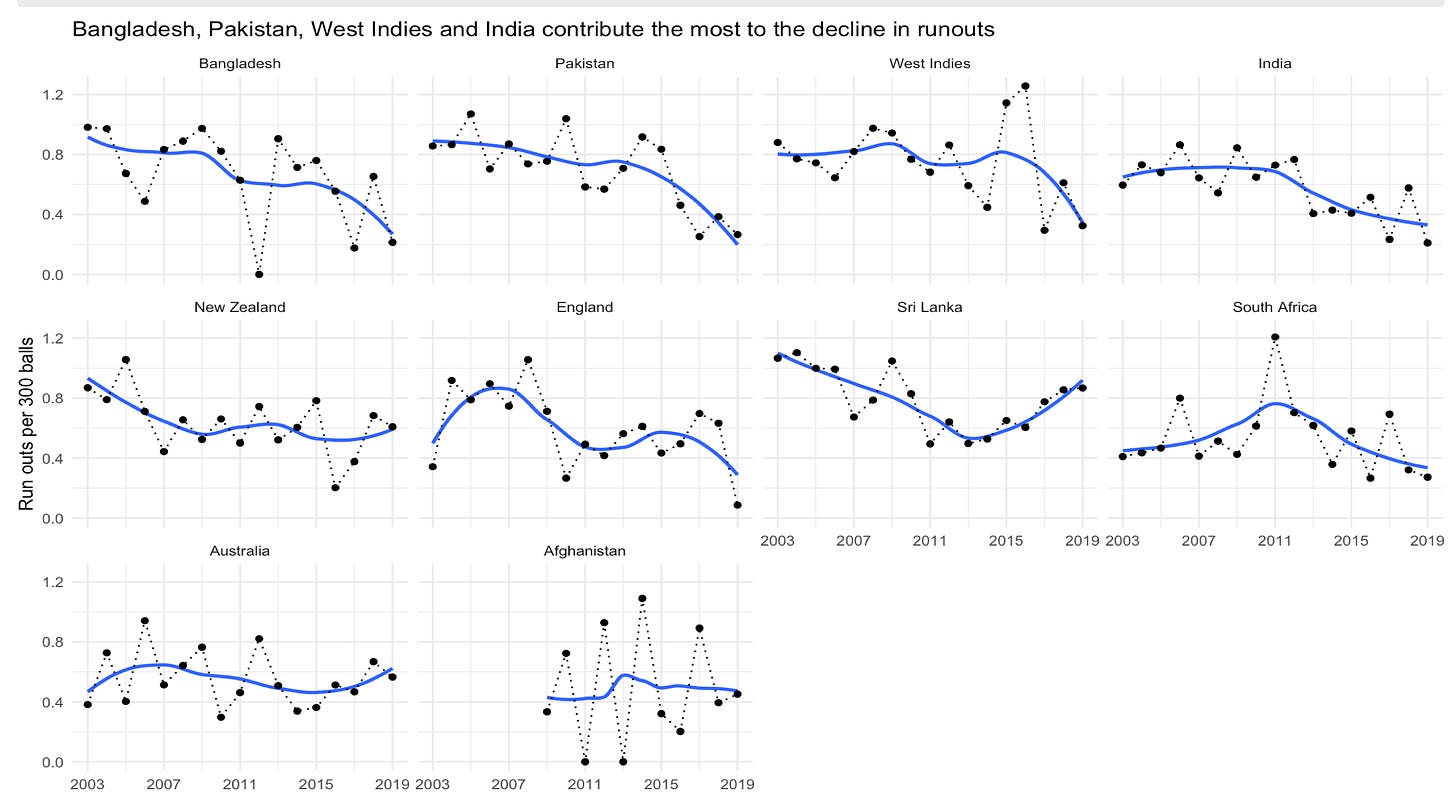

The decline and fall of runouts in the last 16 years is primarily on account of four teams - Bangladesh, Pakistan, West Indies and India.

Sri Lanka saw a sharp decline in runouts until 2012, after which it has increased again. South Africa has shown the opposite trend. Australia, England and New Zealand have largely held steady.

The most obvious explanation to the decline in runouts, apart from the retirement of legendary runners such as Inzamam-ul-Haq, is that teams are simply running less. In 2003, about 7.5% of all balls were hit for boundaries, accounting for 42.5% of the runs. In 2019, nearly 10% of all balls are hit for boundaries, contributing to 48% of the runs.

With the increase in number of boundaries, the number of balls where it is possible to effect a runout has fallen. Moreover, with rampant boundary hitting, teams are seeing less need to convert the ones into twos, and twos into threes. As a consequence, less risky runs are being attempted, and the number of runouts has thus halved.

In a way this trend of fewer runouts is making cricket less interesting. Several iconic moments in cricket history have involved runouts. The first Tied Test. The 1999 World Cup semifinal. Jonty Rhodes’s runout of Inzamam in 1992. Some of Inzamam’s more comical run outs. It is sad that we will see fewer such iconic moments going forward.

Since I imagine (from the data I presented above) that you don’t see too many runouts nowadays, I leave you with this