11. Wagging their tails behind them

Yesterday, Australia beat the West Indies primarily thanks to a splendid rearguard action by Steven Smith and Nathan Coulter-Nile. Having been 38/4, 79/5 and 147/6, Australia finally managed to set a target of 289, which was beyond the reach of the West Indies.

Batting at number eight, Coulter-Nile hit 92 off 65, putting on 102 with Smith. While the batsmen after him didn’t contribute much, Coulter-Nile added another 40 runs with them after Smith got out for 73. In all, the last four wickets for Australia added 141 runs, which is not something you would expect given their performance since the last World Cup in 2015.

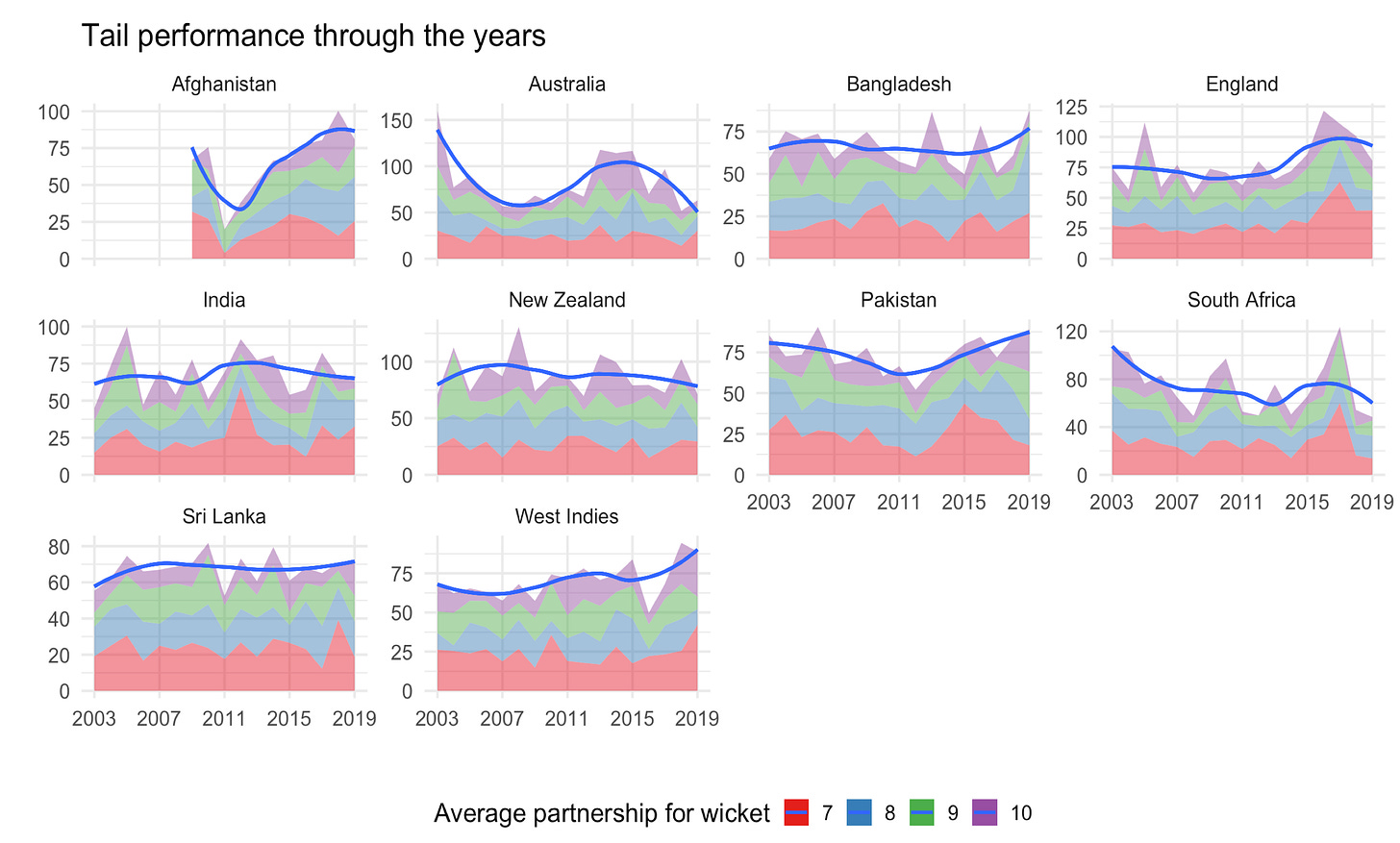

Australia’s seventh wicket partnership in this period has averaged 25, which puts them in the bottom half among teams participating in this World Cup. Their eighth wicket average, 17, is only better than that of the West Indies. However, above-average ninth and tenth wicket partnership averages mean that Australia’s overall tail just about averages in the top half among teams playing in the World Cup.

If we add up the averages for wickets 7 to 10, England has the longest tail, which is not surprising given that so far in the World Cup, they’ve had Adil Rashid, with ten First Class centuries, batting at Number 10. Bangladesh and India have had the worst tails, averaging 64 and 67 respectively.

Interestingly, the quality of tails of a lot of teams has remained consistent over the last 15-16 years. India’s tail has always averaged in the mid 60s. New Zealand’s about 75. Australia and South Africa’s tails have gotten worse over the years, while West Indies’s and England’s have become better. Pakistan’s tail became worse until 2011, after which it has picked up again.

Leave ‘em alone, they will come home

One of the desirable qualities of a lower middle order batsman (someone batting at 5 or 6) is the ability to “shepherd the tail”. The question is if the presence of a top order batsman (someone in the top 6) after 6 or more wickets have fallen down makes a material difference to how much the tail scores (in yesterday’s game, Steven Smith was there to bat with Nathan Coulter-Nile).

While the number of data points available for this might be small (especially since we’re looking at the time window since the last World Cup), we find that for most teams, the presence of a top order batsman batting with the tail makes a material difference to the number of runs added by the tail.

India has the maximum impact of a “shepherd”, with the tail average going from 57 to 95. Bangladesh improves from 53 to 88. At the other end of the scale, South Africa shows only a marginal improvement while Afghanistan (rather weirdly) seems to do better when it’s only tailenders at the crease.

Some tails will continue to wag. Some will just collapse in a heap. Nevertheless a rearguard action by the tail is fun to watch. Unless you are fielding of course!

PS: Time for some gloating. The last edition of this newsletter went out just when the South Africa-India game was to begin. I had written:

South Africa has won the toss and elected to bat first. Perhaps they’ve been stung by their two losses chasing, but by doing so they are allowing India to play to their strength (chasing), and also letting go of the early morning swing which might have helped get Sharma early.

If Sharma does survive his first 30 balls in the chase and go on to get a big one, Faf du Plessis might regret his toss decision once again.

Well, well, well.